For the British, the Franklin Expedition was an opportunity to revitalize the great polar expeditions. The 19th-century challenge was to finally cross the Northwest Passage of the Arctic Ocean between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Encouraged by John Barrow, the Admiralty of the Royal Navy selected John Franklin, an officer who had already distinguished himself in many Arctic expeditions, as commander.

However, the expedition, which set sail on May 19, 1845, got stuck in the ice near King William Island. Between 1846 and 1848, all 129 crew members died of cold, disease, or starvation.

Throughout the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries, numerous scientific studies and investigations have been carried out to understand the causes of the disaster. The Franklin expedition has become a legend.

Who Was Behind the Franklin Expedition?

In the first half of the 19th century, the Royal Navy represented the dominance of British power over the world’s oceans. The expeditions led by the Admiralty were among the events that kept Europe, Canada, and the United States on their toes. Since the early 19th century, the greatest challenge has been to finally cross the Northwest Passage of the Arctic Ocean between the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, the area between Davis Strait and Baffin Bay in the east, and the Beaufort Sea in the west. This region connects Hudson Bay in the southeast and the Arctic Ocean in the northwest.

The impetus for the Northwest Expedition in 1845 came from John Barrow. Second Secretary of the Admiralty since 1804 and an explorer himself, Barrow was an experienced man who had supported many expeditions, including those of William Edward Parry (1821), John Ross (1829), and James Clark Ross (1839). At the age of 82, it was he who persuaded the Royal Navy to undertake an expedition to the northern Canadian Archipelago.

John Franklin was not immediately chosen to lead the expedition. This was because the explorer was 59 years old. However, Barrow’s first choice, William Edward Parry, declined the offer, as did James Clark Ross. At 35, James Fitzjames was considered too young but would still be part of the expedition. George Back was approached for some time but no action was taken.

Francis Crozier, who had participated in six polar expeditions, was ostracized because of his Irish roots but still joined the expedition and was appointed as his assistant. Finally, at the insistence of William Edward Parry, John Franklin, a well-known officer who had participated in many expeditions and battles, including the Battle of Trafalgar, was contacted. This time, Franklin said yes and promised his wife that it would be his last voyage.

Why Was the Franklin Expedition Launched?

The end of the Napoleonic Wars allowed British naval officers to devote themselves to the conquest of unexplored northern territories. During this period of peace, exploration was a way to showcase the human and material prowess of the great Western powers.

The British Admiralty saw polar exploration as an opportunity to make a name for itself, following the extraordinary discoveries made in this region in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries by famous navigators such as Frobisher, Davis, Hudson, Baffin, Knight, Middleton, Hearne, Cook, Mackenzie, and Vancouver. Moreover, from the beginning of the 19th century, a major challenge emerged: after several failed attempts, doubts began to arise about the existence of a navigable passage in the temperate latitudes north of the Canadian archipelago.

Many explorers crossed the icy waters of the Great North, but to no avail. Giovanni Caboto (1450–1498), also known as John Cabot, died there. Martin Frobisher (1535–1594) failed. So did Henry Hudson (1565–1611) and Captain James Cook (1728–1779). More recently, Admiral William Edward Parry (1790–1855) tried his luck between 1821 and 1823.

Rear Admiral John Ross’s (1877–1956) expedition between 1829 and 1833 led to the discovery of the Magnetic Pole and showed that survival in the Far North was possible. Finally, officer James Clark Ross (1800–1862) visited the North Pole several times. None of them managed to cross the famous Northwest Passage.

Who Was John Franklin: The Commander of the Expedition

John Franklin was a British naval officer, explorer, governor, and writer. He was born on April 16, 1786, in Spilsby and died on King William Island on June 11, 1847. He was only 14 years old when he first joined the Royal Navy. Many of his expeditions remain famous, as do the naval battles in which he participated, such as Copenhagen (1801). In 1805, he served under Vice Admiral Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar, where Napoleon Bonaparte‘s attempt to conquer the United Kingdom failed.

In 1818, as a lieutenant, he joined the David Buchan expedition in an attempt to find an ice-free sea at the North Pole. The following year, he was appointed a midshipman on the Coppermine expedition to explore the northern coast of Canada. He returned to the Arctic in 1829, this time to explore the shores of the Beaufort Sea.

In 1823, he married the poet Eleanor Anne Porden, with whom he had a daughter in 1825. In 1828, he married Jane Griffin, a great traveler and Tasmanian pioneer.

John Franklin was knighted by King George V (1829), then awarded the Royal Order of the Guelphs by King William IV (1836). Finally, he was appointed governor of Tasmania on the southeast coast of Australia (1837–1843).

What Resources Were Used for the Franklin Expedition?

On May 19, 1845, at the point of departure at Greenhithe in Kent on the River Thames in England, the resources deployed to ensure the success of the expedition were enormous. The two ships, HMS Erebus (378 tons) and HMS Terror (331 tons), had proven themselves time and again in Antarctica, especially with James Clark Ross. The ships were equipped with state-of-the-art technology, such as iron plate reinforcements and auxiliary steam propulsion systems specifically designed to deal with ice. An internal steam heating system, a daguerreotype camera, three years of canned food and a library of more than 1,000 books per ship were installed on board.

The expedition’s mission also included various zoological, botanical, magnetic, and geological studies. The young, robust, and experienced crew was selected with this goal in mind. Under the command of John Franklin and his assistant, Captain Francis Rawdon Crozier, the crew consisted of 129 seamen, mostly British, including 24 officers and two glaciologists, Reid and Blanky. In 2017, unconfirmed DNA analysis showed that four women may have taken part in the expedition.

What Was the Franklin Expedition’s Route Like?

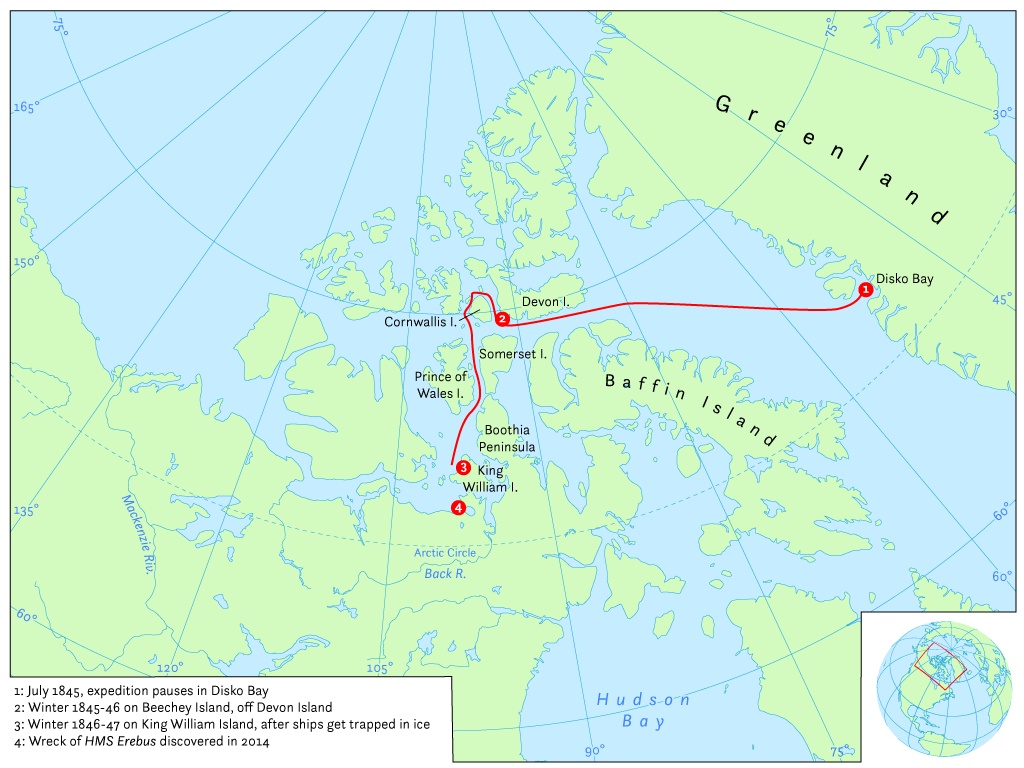

By order of the Admiralty, Franklin’s route passed through the port of Stromness in Orkney in the north of Scotland. At Disko Bay on the west coast of Greenland, the ship received new equipment and fresh meat. It was here that the crew sent their last letters to their loved ones. The expedition was last seen in the Baffin Sea in August 1845, as the Erebus and Terror searched for favorable conditions to cross Lancaster Sound between Devon Island and Baffin Island. This is where the last European record of that period ended.

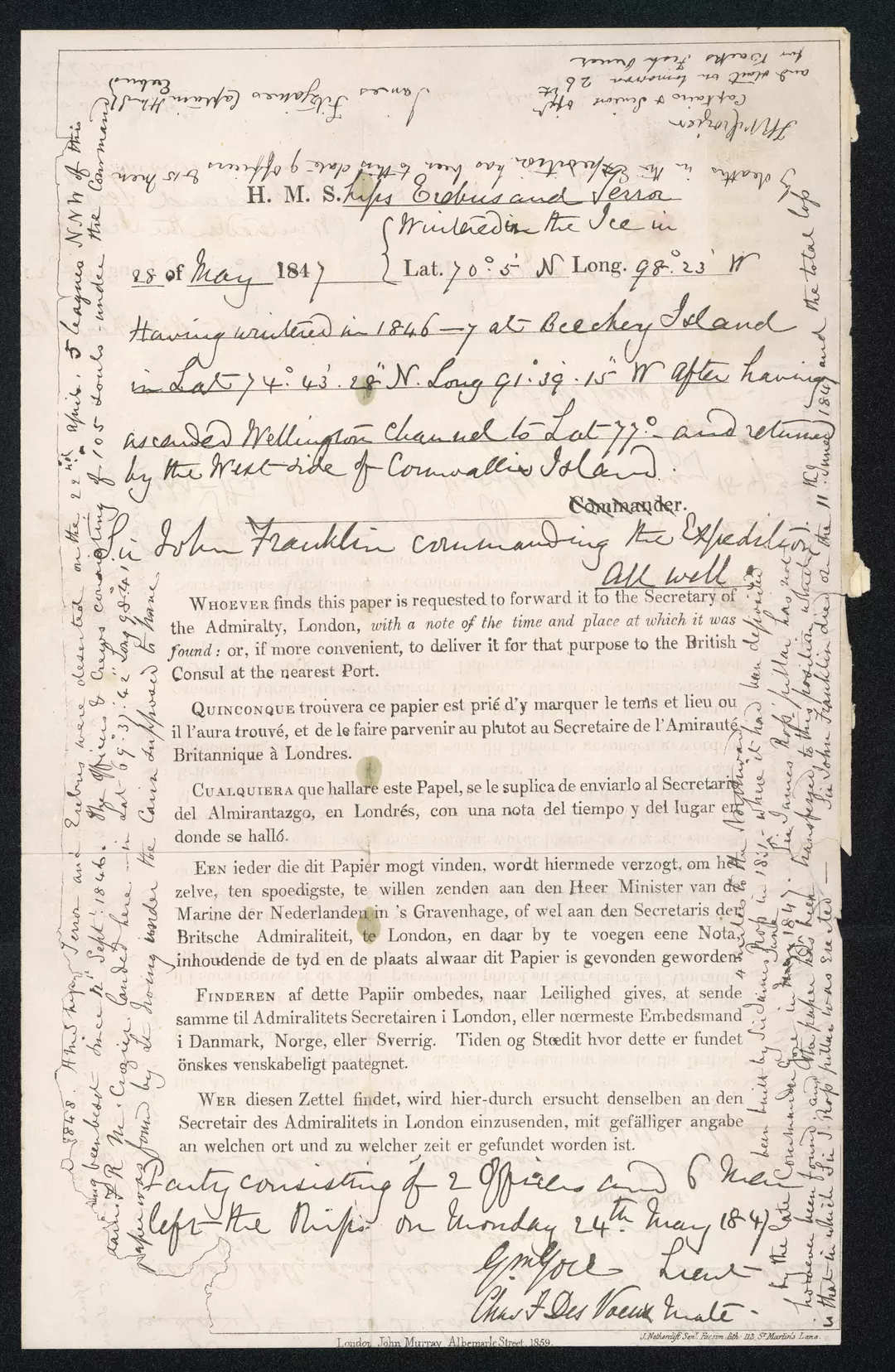

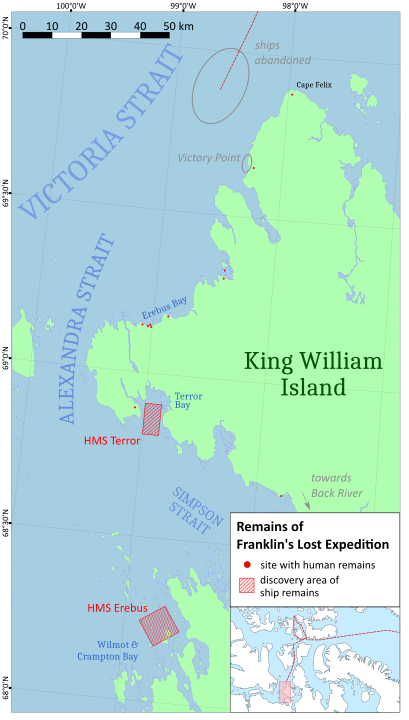

The rest of the voyage became a riddle that other expeditions, taking advantage of recent technological advances, would solve over the next 150 years. Franklin and his men spent the winter of 1845–1846 on Beechey Island, where three crew members were found buried. In 1846, the ships headed south to Peel Sound near King William Island, where they became stranded in the ice. According to a note left on the island by Crozier and Fitzjames dated April 25, 1848, by June 11, 1847, 24 men, including Franklin himself, were already dead. The crew left King William Island on April 26, 1848, planning to head for the Back River (present-day Nunavut, Canada) and find a way out to the Pacific.

Why the Franklin Expedition Failed?

In Franklin’s chosen passage, the ice on the west coast of King William Island would not necessarily melt in the summer, at least not that summer. Unlike the eastern shore chosen by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen (1872–1928) between 1903 and 1906, this passage was not successfully traversed.

Stranded in the ice of the Victoria Strait (between Victoria Island and King William Island) for two winters, the crew was ill-equipped for land travel.

Cultural disagreements probably prevented Europeans from adapting to Inuit survival methods. In addition, testimonies from Inuit tribes indicate that men on the expedition starved to death; research suggests that some died of disease. In short, the crew was ill-prepared for such an expedition and had little knowledge of the sea routes.

What Were the Losses Caused by the Franklin Expedition?

In addition to the consequences of cold and starvation, most crew members died from a combination of diseases uncovered by forensic studies from the 1980s onwards, following field investigations and excavations. Many men died of pneumonia, colds, tuberculosis, lead poisoning, and possibly scurvy. The existing drinking water system on board contained high levels of lead. The same was true for a number of lead enclosures, such as sealed lead boxes.

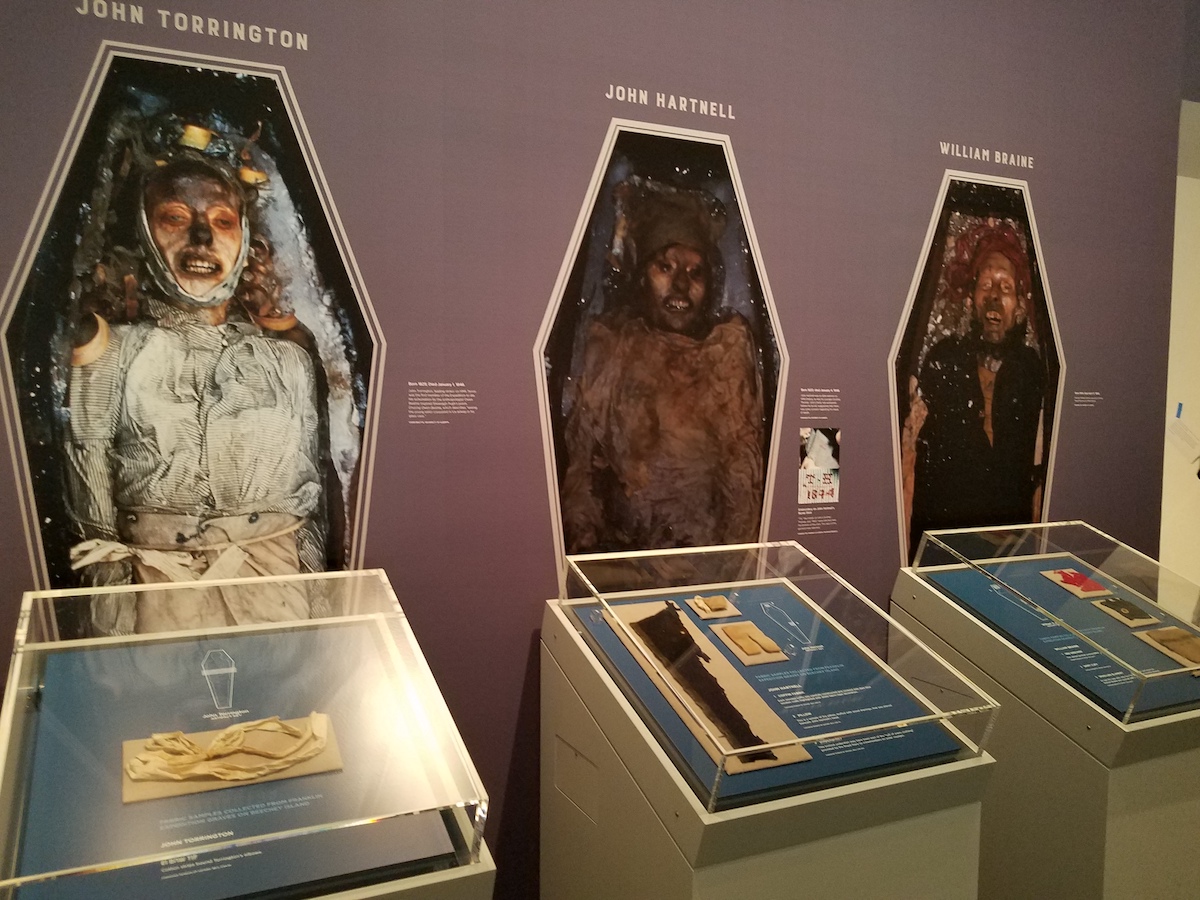

These findings were confirmed by the autopsy of the “mummified” bodies of John Torrington, John Hartnell, and William Braine found on Beechey Island in August 1984. Their graves were preserved virtually undisturbed for 138 years in impermeable permafrost, a component of ice. John Franklin died on King William Island on June 11, 1847. Finally, some dark spots have been brought to light: a forensic examination of the bones found cut marks “consistent with butchery”, raising suspicions that the last survivors resorted to cannibalism.

What Were the Results of the Failure of the Franklin Expedition?

After two years without news of the expedition, the Admiralty ordered the first search. One team was sent overland along the Mackenzie River to its mouth on the shores of the Arctic Ocean. Two other teams were sent by sea to reach the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. However, all three failed. In 1850, 11 British ships and 2 American ships reached the shores of Beechey Island, where the first remains were discovered. These were, in particular, the graves of three sailors, John Torrington, John Hartnell, and William Braine.

Subsequent expeditions, especially those of John Rae in 1854 and James Anderson in 1855, reported Inuit testimony and found material and other human remains, especially near the mouth of the Back River and on Montreal Island in Chantrey Bay. Great Britain then declared the crew officially dead on March 31, 1854, and halted the search.

Jane Griffin, John Franklin’s wife, decided to finance a new expedition under the command of Francis Leopold McClintock, which sailed on July 2, 1857. This voyage led to the recovery of some important documents, such as this note dated April 25, 1848, showing that the two ships had been stranded in the ice since September 12, 1846.

In the 20th century, research resumed. In June 1981, the 1845–48 Franklin Expedition Forensic Anthropology Project (FEFAP) was launched, allowing modern forensics to better identify new human remains. The wreck of HMS Erebus was found south of King William Island on September 7, 2014. The wreck of HMS Terror was found off the southwest coast of King William Island on September 12, 2016. Currently jointly managed by Parks Canada and local Inuit, the wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site are closed to the public.