Following France’s defeat at the hands of Germany in World War II, the Third Republic was replaced by the Vichy France on July 10, 1940. Marshal Pétain was granted absolute power and promptly established the “French State,” relocating his government to the free zone city of Vichy. The marshal then took center stage as the World War I‘s heroic “providential man,” the man who would help France recover from its devastating loss to Germany, which had occupied the country’s northern and western regions. With daily interactions with the Germans, the Marshal used all the power at his disposal to introduce new principles; this was collaboration. The Germans evacuated France upon the arrival of the Allies on August 20, 1944, and General de Gaulle assumed the presidency of the Provisional Government of the French Republic, bringing an end to the Vichy regime.

How did the Vichy regime collaborate with Germany?

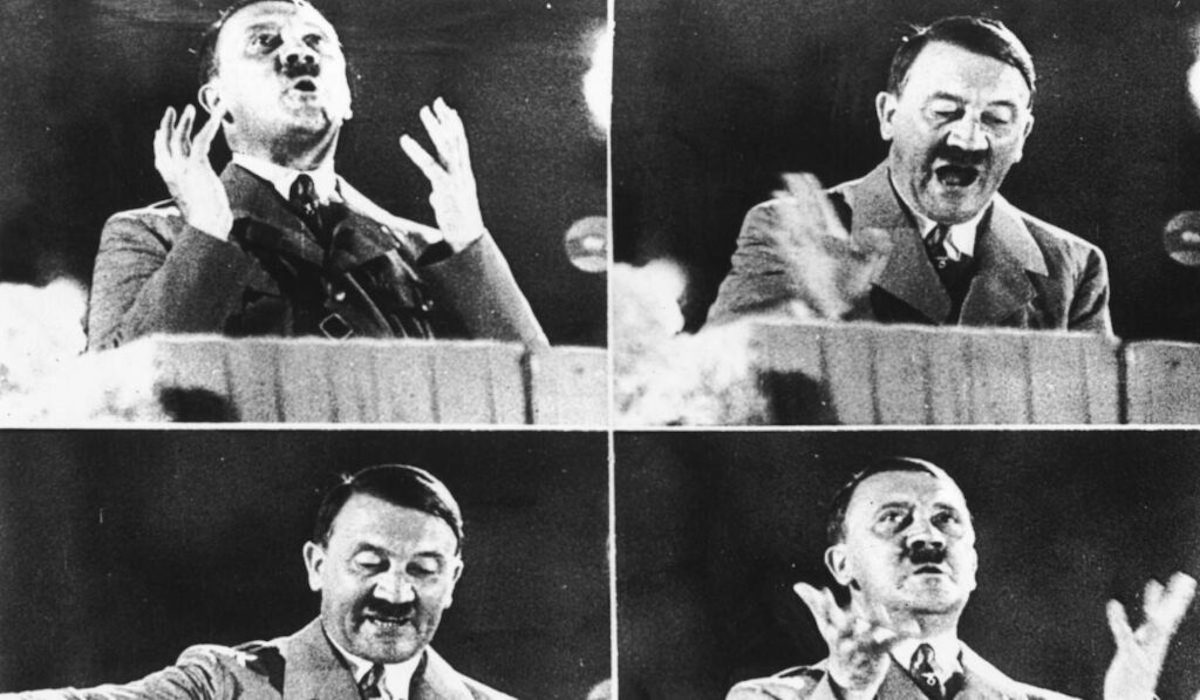

The “French State,” or Vichy France, was nominally independent after the German occupier handed over administration of France to them. Towards the end of October 1940, Philippe Pétain gave a speech in which he openly supported collaboration. There was a meeting between Hitler and the Marshal in Montoire-sur-le-Loir on October 24th, 1940. Immediately following the German invasion of the free zone on November 11, 1942, collaboration intensified. Loan of labour (STO), increased repression of opponents, establishment of the SOL and then the French Militia, economic measures favoring Germany, etc. all served German ideology under the Vichy regime. Moreover, anti-Semitic laws (such as the mandatory wearing of the yellow star and the confiscation of property) were enacted, as well as the establishment of a General Commissariat for Jewish Questions (CGQJ) and Jewish roundups like the Vel’ d’Hiv’.

Was the Vichy France an anti-republican regime?

The anti-republican Vichy regime had Marshal Pétain exercising legislative and executive powers and had abolished Parliament. It was a dictatorship, in which one man made all the decisions without consulting the people. The regime’s anti-republican tenor was bolstered in 1943 when a militia was formed to combat resistance fighters and apprehend Jews. After a short period of time, references to the “French Republic” were removed from all government publications.

What was the composition of the Vichy government?

Secretary of State members served alongside French President Philippe Pétain. François Darlan succeeded Pierre-Étienne Flandin as Vice President of the Council after Pierre Laval stepped down. In April 1942, Pierre Laval became the Head of Government of Vichy France, a position he combined with his duties as Minister of the Interior, Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Minister of Information. Financial Minister Yves Bouthillier was succeeded by Pierre Cathala. Pierre Pucheu (Minister of the Interior) and Paul Baudouin (Minister of Foreign Affairs and then Minister of Information) were just two examples of the many different people who have held high offices in France. There were then separate ministers of state in charge of the air force, the navy, and the war.

What were the symbols of the Vichy France?

The motto “Travail, Famille, Patrie” (Work, Family, Homeland) replaced the French Republic’s former motto of “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité” (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity) as the defining symbol of the Vichy regime, its ideology of “national revolution,” and its new moral order. The francisque, the national symbol, comes next. It’s a battle axe with both sides decorated in the blue, white, and red of France, and it’s been kept in mint condition. It was used on all government publications, advertisements, and trophies. The song “Maréchal, nous voilà!” was taught to every schoolchild in Vichy France and quickly became the unofficial anthem of the regime.

KEY DATES IN VICHY FRANCE

April 5, 1939 – Albert Lebrun was re-elected President of the Republic

The newly re-elected French President Albert Lebrun fought against signing an armistice with Adolf Hitler’s Germany. Eventually, he had to cede power to Marshal Pétain, who was elected president of the Council. In the end, authorities in the Austrian Tyrol captured and imprisoned Albert Lebrun.

Pétain was elected Council President on June 16, 1940

Pétain served as President of the Council of the Third Republic prior to becoming head of state of France (Vichy regime). On the same day he took office, he was replaced by a government formed after Paul Reynaud’s resignation. As required by the Constitution, this change had taken place. When Pétain was in charge, his administration went by that name. The Marshal was already 84 years old. After signing the armistice on June 22, 1940, Philippe Pétain immediately established a new government in Vichy.

France and Germany sign an armistice on June 22, 1940

France’s Council President Philippe Pétain officially ends hostilities with Germany. The country of France was effectively divided in half, with the northern and western regions under German control and the southern region remaining independent. There was a line drawn in the sand that divided the two halves. The Marshal set up his new government in the southern city of Vichy.

July 2, 1940 – The Pétain government settled in Vichy

Pétain’s government established its headquarters in the free zone city of Vichy. Considering its proximity to the demarcation line with the occupied zone and its convenient train connections to Paris, this was a calculated move. The hotel’s facilities also made it simple to house the government officials. Since the government settled here, its rule was known as the Vichy regime.

French State was founded by Pétain on July 10, 1940

On this day, the “French State” officially began. The Third Republic ended when Marshal Pétain was given absolute power by the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. Assembly business was settled at the Grand Casino in Vichy. There were 569 in favor of Marshal Pétain and 80 opposed; 19 people didn’t vote. To legitimize the establishment of the “French State,” now known as the Vichy France, a new constitution was enacted. “Work, Family, Country” became the new national motto of France.

July 12, 1940 – Pierre Laval vice-president of the Council

Phillipe Pétain named Pierre Laval vice president of the Council and his successor on July 12. After the Allies won the war in Europe in August 1944, the “French State” was no more.

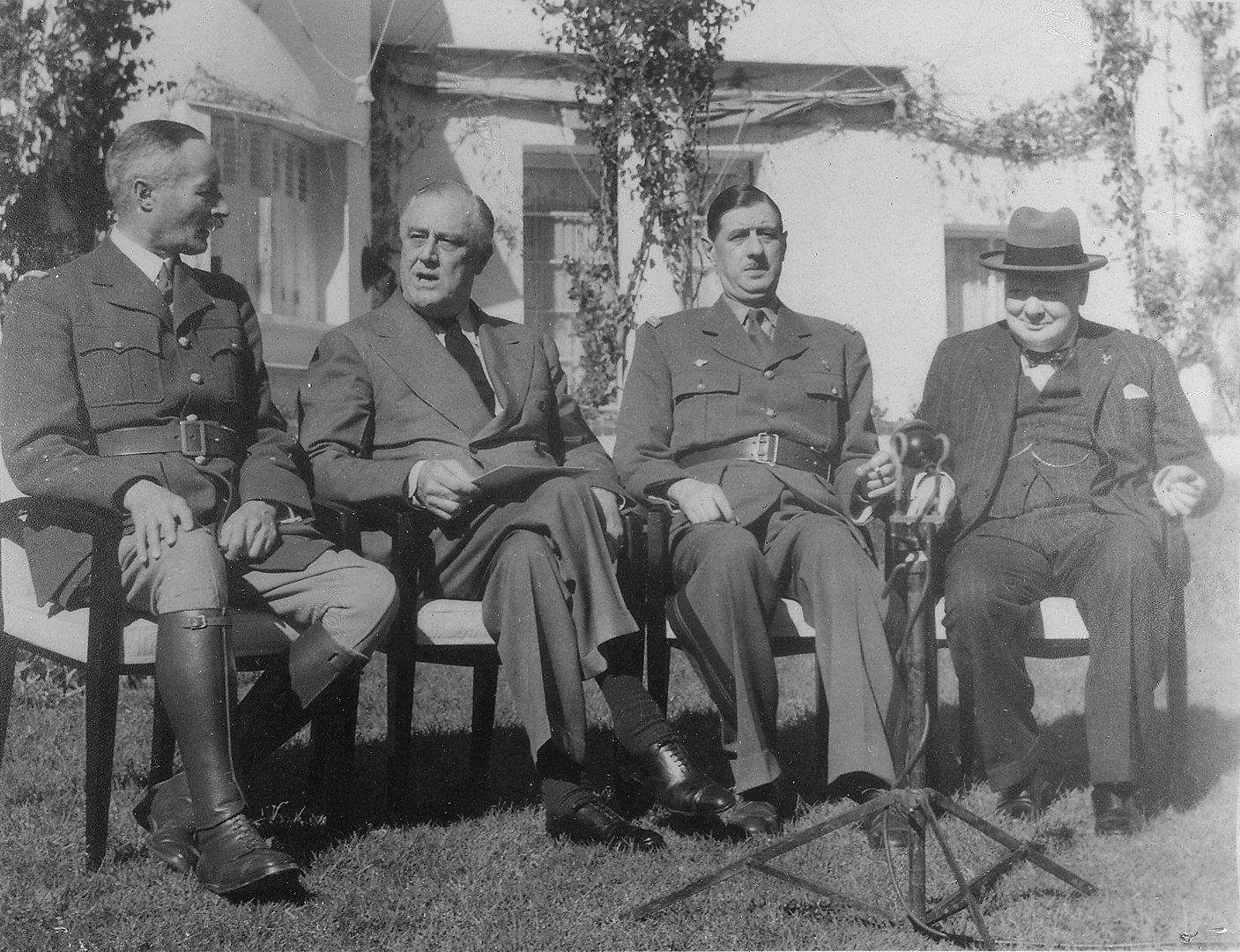

Churchill officially recognized de Gaulle as the legitimate leader of France on August 7th, 1940

Churchill’s official endorsement gave General de Gaulle the confidence he needed to take decisive action. Britain officially recognized the independence of the Free French Forces (FFL) after he signed agreements with Churchill on that day. Agreements like these provided the FFL with the funds it needed to take action and ensured that French possessions would be returned upon the country’s liberation.

Léon Blum was taken into custody on September 15, 1940

Léon Blum, the founder of major social laws and the Popular Front’s president in 1936, voted against giving Marshal Pétain full powers on July 10, 1940. As both a Jew and a socialist, he was targeted for arrest by the Vichy regime on September 15 and sent to Chazeron prison, where he attempted to coordinate resistance efforts from behind bars. After being tried in Riom and found guilty of leading France to defeat, he was turned over to the Germans and sent to Buchenwald.

Position of Jews in the Neutral Zone as of October 3, 1940

The Vichy government issued a new law regarding the status of Jews without any influence from the Nazi regime. According to Article 1, a person was considered Jewish if they have at least three Jewish grandparents or two non-Jewish grandparents whose spouse was Jewish. This was the first of a series of measures that will progressively worsen over time. Jews were restricted from working in many fields. Marshal Pétain’s collaboration led to the deportation of 75,721, including 6,012 children.

Pétain and Hitler shake hands on October 24, 1940

This handshake took place at the Montoire meeting and was captured on film forever. This was a visual representation of the Nazi regime’s cooperation with the Vichy government. After their interview at the train station, Hitler and Pétain continued their discussion in Hitler’s private carriage. On October 30, Pétain addressed the French people and urged them to “collaborate,” explaining that he had sought to improve France’s situation with the war’s victor.

December 13, 1940: Pierre Laval was dismissed

After being accused of having too close of ties to Germany, Philippe Pétain removed Pierre Laval as vice president of the Council and put him under house arrest. Adolf Hitler did not agree with the new Vichy government leader, so he had Laval released. In April of 1942, Pierre Laval regained prominence when he was appointed prime minister, foreign minister, interior minister, and minister of information all at the same time.

French strike ban on October 4, 1941

The law of October 4, 1941, known as the “Labor Charter”, was passed by the Vichy regime. It prohibited strikes and established the principle of single, compulsory unions.

The Riom trial began on February 19, 1942

On February 19, 1942, the Vichy regime initiated the Riom trial in an effort to establish the guilt of Third Republic politicians for the defeat of 1940. The likes of Léon Blum and Édouard Daladier, among others, were among those who stood accused. However, the defense presented compelling evidence that the loss was a result of military failure rather than political missteps. The trial was put on hold because it did not result in an indictment. With his newfound authority, Marshal Pétain decided to hand down a conviction himself.

22 February 1942 – Creation of the Service d’Ordre Légionnaire (SOL)

Joseph Darnand established the “Service d’Ordre Légionnaire” (Legionary Order Service) on February 22, 1942. They were a Vichy regime military group. They took an oath to “fight against democracy and the Jewish leprosy” and pledged their allegiance to the Nazi regime in exchange for membership in this openly collaborator army. After initially supporting the Vichy regime, the Service d’ordre légionnaire eventually broke away and aligned itself with less extreme collaborationist regimes. Joseph Darnand continued to lead the SOL after it morphed into the French Militia in 1943.

Vel’ d’Hiv’ raid, 17 July, 1942

A total of over 13,000 Jews, including around 4,100 children, were arrested in the Paris area overnight. René Bousquet, the French police’s General Secretary, was the one to carry out the order from the Vichy government. The Vel’ d’Hiv’ round-up got its name from the days the prisoners were stacked up at the Velodrome d’Hiver. Their next stop was Drancy, before they were shipped off to Auschwitz.

German forces invade the free zone on November 11, 1942

To counter the Allied invasion of North Africa, Adolf Hitler launched “Operation Attila” against France on November 8. The Germans invaded the southern part of the country, which had been a “free zone,” despite the name. Germany exerted full control and influence over the Vichy government.

February 16, 1943 – Institution of the STO

Vichy France passed a law instituting the Obligatory Labor Service because the “relief” and volunteer systems weren’t enough to meet German demand for labor. Every single man between the ages of 21 and 23 was shipped off to Germany to work for a total of four years. Some of the young men, however, defied the authority. People who didn’t want to sign the STO formed the maquis.

April 26, 1945 – Pétain took himself prisoner

Philippe Pétain, facing charges of “intelligence with the enemy” and “high treason,” decided to surrender as a prisoner in Switzerland. A few months later, there was no question about the verdict: he was sentenced to death. The sentence was changed from death to life in prison by General de Gaulle.

July 23, 1945 – Philippe Pétain’s trial opens

Marshal Pétain, a hero of World War I, went on trial in the High Court of Justice on July 23, 1945. In his trial, where he remained silent, questions were raised about his possible collaboration and his reasons for sparing France. It took a long time, but he was ultimately found guilty and given the death penalty. He was given a life sentence instead of death because General de Gaulle intervened on his behalf.

October 4, 1945: Pierre Laval’s trial opens

Pierre Laval, who had no idea how unpopular he was, learned the hard way during his trial, when he was subjected to jeers and insults from the crowd. The trial was hastily wrapped up, and the defendant was found guilty of high treason and conspiracy against the internal security of the State. For this reason, Pierre Laval was given the death penalty. On October 15 of that year, he was killed inside the Fresnes prison.