Vivandières, cantinières, washerwoman, prostitutes… Women were fully part of the Grande Armée. Incorporated into units or offering their services to passing troops, these women improved the well-being of soldiers who were far away from their families. Some of them even became prominent figures in the Napoleonic epic, known for their heroism, courage, and, in certain cases, for their unique careers as soldiers!

Cantinières: Vivandières, and Laundresses

The cantinier was a man, usually a non-commissioned officer, but it was generally accepted that he could have a woman with him to help in the kitchen (one per battalion). These women had the sole mission of preparing meals, although, in practice, they sometimes competed with the vivandières.

Two types of women were officially allowed to follow the Imperial army: laundresses and vivandières. Their numbers were strictly regulated, with a maximum of four per battalion and two per squadron, army headquarters, or division. Laundresses took care of the soldiers’ laundry, and under the 1809 regulations, they were permitted to have a packhorse to carry their supplies. These were typically soldiers’ wives, and as non-combatant military personnel, they were entitled to a security card (which confirmed their role), lodging, and bread.

They also wore a regulatory medal.

Vivandières, on the other hand, sold food, drink, and sometimes small items to the soldiers. They were allowed to have a cart pulled by two horses. Comparable to a modern army’s canteen service, they essentially ran a mobile shop. Their numbers were limited in the same way as the laundresses. They did not receive any salary but were still officially part of the military personnel: they needed a security card issued by military authorities, had the right to use military hospitals during wartime, and had to be present for roll calls conducted by column commanders.

Discipline was strict. Laundresses and vivandières who missed a roll call faced fines for the first offense, imprisonment for the second, and confiscation of their horses and cart for the third. Worse, if one was accused of looting or facilitating looting (vivandières were sometimes involved in hiding stolen goods to sell for themselves), her cart would be burned along with all her belongings, and the woman, dressed in black, would be paraded through the camp and expelled.

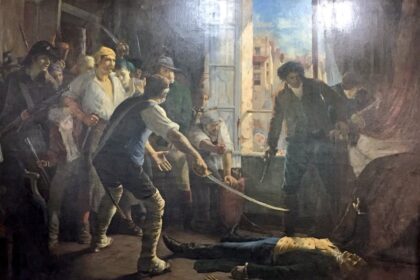

But that was not the most humiliating punishment. During the Spanish campaign, the penalty for a woman following the army without authorization was severe: she would be stripped, shaved all over, covered in shoe polish, forced to march in front of the troops, and sent to the rear.

Nevertheless, vivandières were among the iconic figures of the Grande Armée. During marches, they were relatively protected, with their carts placed at the rear of the convoy between the column and the rear guard. The vivandière became a symbol in the historiography of the Imperial army, improving the soldiers’ daily lives with her goods and small cask of brandy, and sometimes coming to the aid of the wounded on the battlefield. The vivandière is one of the few female figures in a predominantly male institution. In the 19th-century romantic imagination, she also came to represent a kind of substitute mother for younger conscripts.

Among the best-known vivandières was one nicknamed Marie Tête-de-Bois. Marie married a grenadier in 1805, who was killed in Paris in 1814. That same year, their son was killed at the Battle of Montmirail, and Marie herself was wounded while retrieving his body. Having served in seventeen campaigns, Marie Tête-de-Bois was with the Guard during the Hundred Days in 1815. It was in this final campaign of the Empire that she met her death, struck by a bullet that pierced her cask. As she crawled among the dead, a second bullet is said to have hit her face. A dying grenadier reportedly joked that she wasn’t very pretty like that, to which she supposedly replied that she could still boast of having been a daughter, wife, mother, and widow of soldiers.

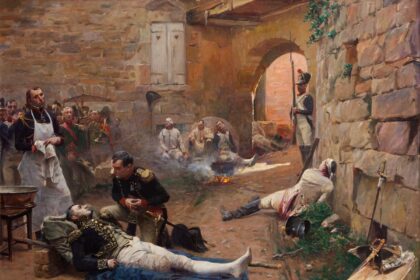

Catherine Balland, from the 95th Line Infantry Regiment, was honored by the painter Lejeune, who depicted her in his painting of the Battle of Chiclana. She was awarded the Legion of Honour in 1813.

Prostitutes and Campaign Loves

The Grande Armée never had an official or semi-official brothel, as was later the case in the French army. Nevertheless, prostitutes (often referred to as “grisettes”) closely followed the troops to offer their services. They inevitably became the main vectors of venereal diseases, which greatly occupied military doctors. Some prostitutes even approached soldiers directly, as evidenced by General Friant’s order on September 18, 1811, instructing to “arrest the runners who sneak into the camps.”

The Grognards also took advantage of the services of local prostitutes in the cities they passed through, both in France and abroad. These women were either professionals or poor souls driven to prostitution by the misery caused by war. In 1806, Berlin women prostituted themselves for a bit of bread, and in 1812, well-off Moscow women, starving, were forced into prostitution, even offering their daughters to the French soldiers.

In addition to professional sex workers, the soldiers of the Grande Armée also engaged in relationships with local women during their campaigns, though these relationships were often fleeting. Upon the imperial army’s departure from Berlin in 1806, it was estimated that 2,000 women were pregnant.

However, some of these campaign relationships did lead to marriages. Starting in 1808, soldiers had to obtain permission from the administrative council of their regiment to marry their chosen partner (officers had to seek authorization from the Minister of War). Despite this new status, it did not change their military situation. In 1810, a decree even provided financial support for soldiers marrying a “respectable girl.

”

Women Soldiers

Officially, Napoleon’s Grande Armée was not supposed to have women soldiers. Even during the Revolution, the profession of arms was denied to women, as military service was ideologically linked to citizenship (and, by extension, the right to vote). However, there were a few exceptions that proved the rule, such as Marie-Thérèse Figueur (1774 – 1861).

Orphaned and placed with a cloth merchant in Avignon, she pleaded with her uncle in 1792 to let her wear a uniform.

Her uncle, who commanded a company of gunners, placed her in a counter-revolutionary federalist troop. She was captured along with her uncle by the Legion of Allobroges, and General Carteaux offered them the chance to switch sides, which they accepted. Young Figueur participated in the siege of Toulon in 1793 with the Legion of Allobroges before switching units, first joining the 9th Regiment and later the 15th Regiment of Dragoons. She was nicknamed “Sans-Gêne” (she later inspired the play by Victorien Sardou and Emile Moreau).

With this cavalry regiment, she participated in several campaigns: the Eastern Pyrenees, Germany, the Army of the Rhine, the Swiss campaign, and the Italian campaign.

On November 4, 1799, her horse was killed beneath her, she was wounded, and she was captured at the Battle of Savigliano (Piedmont). She was brought before Prince de Ligne, who allowed her to join his army.

Under the Consulate, in 1800, she was forced into retirement but managed to reintegrate the 9th Dragoons, with whom she participated in the 1805 campaign, including the battles of Ulm and Austerlitz. In 1806, she fought in the Battle of Jena but fell ill and was repatriated to France. Once recovered, she joined the Young Guard and went to fight in Spain, where she was again taken prisoner at Burgos.

She was handed over to a Scottish regiment, which delivered her to the Portuguese.

Figueur was then transferred to a women’s prison and later to Southampton, where she remained until the end of the Empire. Upon her return to France during the Restoration, Marie-Thérèse opened a guesthouse for officers and married an old comrade, the sergeant Sutter, late in life.

Although rare, we know of other examples of women soldiers, such as Marie Angélique Duchemin, who distinguished herself during the Revolutionary campaigns and for whom Marshal Sérurier tried to obtain the Legion of Honour during the Empire. Other European armies also had such examples, as in the Prussian army. It was only when mortally wounded at Dannenberg (1813) that soldier Renz confessed to being a woman—it was Eleonore Prochaska, who had enlisted during the Prussian War of Liberation as a drummer and later as a line soldier, successfully concealing her true identity.