In 1787, France entered an economic downturn that gradually turned into a crisis: production was declining, and cheaper British goods flooded the French market. This was compounded by poor harvests and natural disasters, which led to the destruction of crops and vineyards. Additionally, France had spent heavily on unsuccessful wars and support for the American Revolution. Revenue was insufficient (by 1788, expenses exceeded income by 20%), and the treasury took out loans, the interest on which became unbearable. The only way to increase state revenues was to strip the first and second estates of their tax privileges.

- The French Revolution and the Establishment of a Constitutional Monarchy

- Execution of the King and the Establishment of the Republic

- The Jacobin Dictatorship: The Thermidorian Coup, and the Establishment of the Consulate

- Napoleon Bonaparte’s Coup and the Establishment of the Empire

- Restoration of the Bourbons and the July Monarchy

- The Revolution of 1848 and the Establishment of the Second Republic

- The Coup of 1851 and the Second Empire

- The Revolution of 1870 and the Establishment of the Third Republic

Attempts by the government to abolish the tax privileges of the first two estates failed, encountering resistance from the noble parliaments (the highest courts of the Old Regime period). The government then announced the convening of the Estates-General, which included representatives of all three estates. Unexpectedly for the crown, this sparked a broad public awakening: hundreds of pamphlets were published, and voters wrote instructions for their deputies. Few aimed for a revolution, but all hoped for change.

The impoverished nobility demanded financial support from the crown while hoping for a limitation of its power; peasants protested against seigneurial rights and hoped to acquire land ownership; among the townspeople, Enlightenment ideas about equality before the law and equal access to positions became popular (in January 1789, the widely known pamphlet by Abbot Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès “What is the Third Estate?” was published, containing the following passage: “1. What is the Third Estate? — Everything. 2. What has it been heretofore in the political order? — Nothing. 3. What does it want to be? — Something“).

Relying on Enlightenment ideas, many believed that the supreme power in the country should belong to the nation, not the king, that absolute monarchy should be replaced by a limited one, and that traditional law should be replaced by a constitution — a set of clearly defined laws applicable to all citizens.

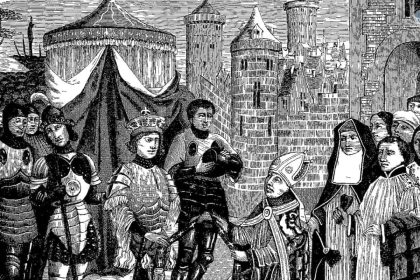

The French Revolution and the Establishment of a Constitutional Monarchy

On May 5, 1789, the Estates-General convened in Versailles. Traditionally, each estate had one vote. The deputies of the Third Estate, who were twice as numerous as those of the First and Second Estates, demanded individual voting, but the government refused. Moreover, contrary to the deputies’ expectations, the authorities only put forward financial reforms for discussion. On June 17, the deputies of the Third Estate declared themselves the National Assembly, representing the entire French nation. On June 20, they swore not to disperse until a constitution was drafted. Shortly afterward, the National Assembly proclaimed itself the Constituent Assembly, thereby declaring its intention to establish a new system of government in France.

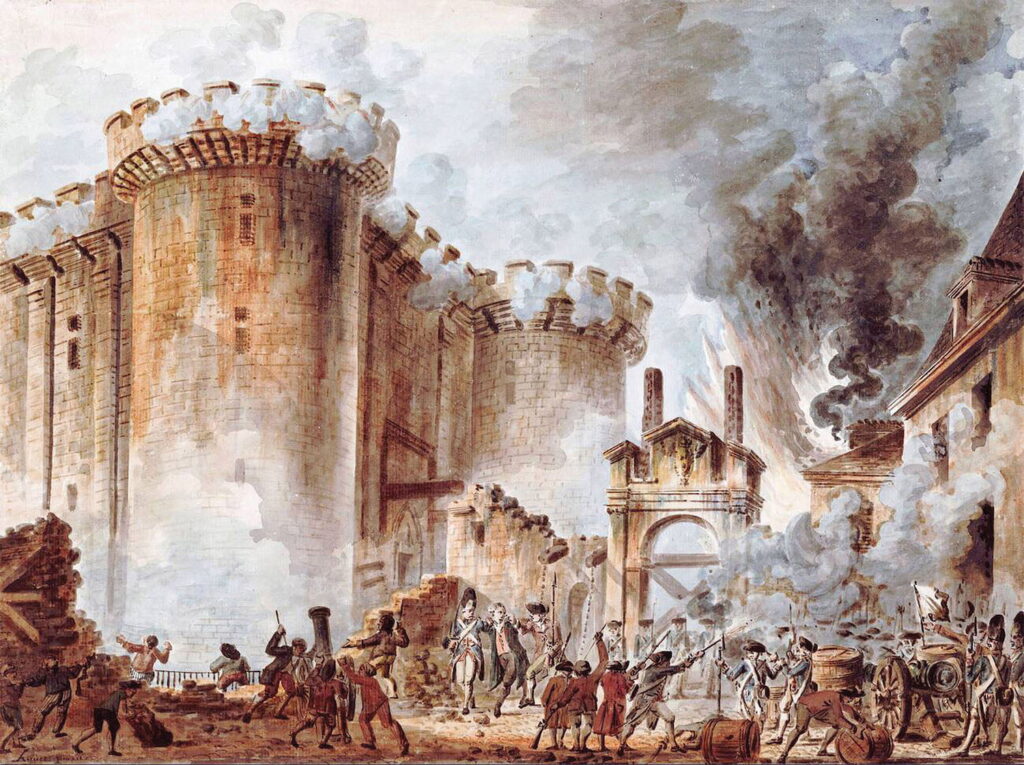

Soon, rumors spread in Paris that the government was moving troops to Versailles and planned to disperse the Constituent Assembly. A rebellion began in Paris; on July 14, hoping to seize weapons, the people stormed the Bastille (Storming of the Bastille). This symbolic event is considered the beginning of the revolution.

Following this, the Constituent Assembly gradually became the supreme authority in the country. Louis XVI, who sought to avoid bloodshed at any cost, eventually approved all its decrees. Thus, from August 5 to 11, all peasants became personally free, and the privileges of the two estates and individual regions were abolished.

Overthrow of the Absolute Monarchy

On August 26, 1789, the Constituent Assembly approved the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. On October 5, a crowd marched to Versailles, where Louis XVI was, and demanded that the king move with his family to Paris and approve the Declaration. Louis was forced to agree — and absolute monarchy ceased to exist in France. This was enshrined in the constitution adopted by the Constituent Assembly on September 3, 1791.

After adopting the constitution, the Constituent Assembly dissolved. Laws were now approved by the Legislative Assembly. Executive power remained with the king, who had become a servant of the people’s will. Officials and priests were no longer appointed but elected; church property was nationalized and sold off.

Symbols

Execution of the King and the Establishment of the Republic

On August 7, 1791, in the Saxon castle of Pillnitz, Prussian King Frederick William II and Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II (brother of Louis XVI’s wife, Marie Antoinette), under pressure from aristocrats who had emigrated from France, signed a document declaring their readiness to support the King of France, including militarily. The Girondists, republic supporters, used this to persuade the Legislative Assembly to declare war on Austria, which occurred on April 20, 1792. When French troops began suffering defeats, the royal family was blamed.

The Overthrow of the Constitutional Monarchy

On August 10, 1792, a rebellion occurred, resulting in Louis being deposed and imprisoned on charges of treason against national interests. The Legislative Assembly dissolved itself: now, in the absence of a king, a new constitution needed to be drafted. For this purpose, a new legislative body was convened — the elected National Convention, which first proclaimed France a republic.

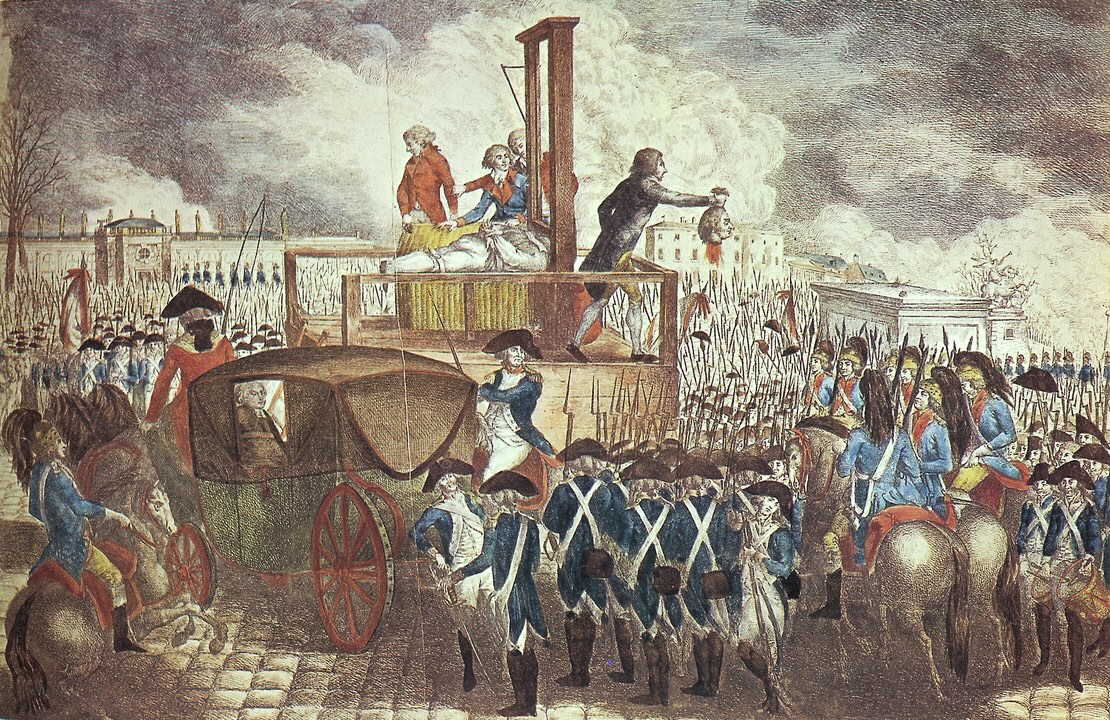

In December, the trial began, which found the king guilty of conspiracy against the nation’s freedom and sentenced him to death.

Symbols

- La Marseillaise: A march written by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle (a military engineer, poet, and composer) on April 25, 1792. In 1795, La Marseillaise became the national anthem of France, lost this status under Napoleon, and finally regained it in 1879 during the Third Republic. By the second half of the 19th century, it had become an international song of left-wing resistance.

The Jacobin Dictatorship: The Thermidorian Coup, and the Establishment of the Consulate

Despite the execution of the king, France continued to face setbacks in the war. Inside the country, monarchist uprisings erupted. In March 1793, the Convention established the Revolutionary Tribunal to try “traitors, conspirators, and counter-revolutionaries,” followed by the Committee of Public Safety, which was meant to coordinate the country’s domestic and foreign policy.

Expulsion of the Girondins

The Girondins gained significant influence in the Committee of Public Safety. Many of them did not support the king’s execution and the introduction of emergency measures; some were outraged that Paris was imposing its will on the country. Competing with them, the Montagnards turned dissatisfied urban poor against the Girondins.

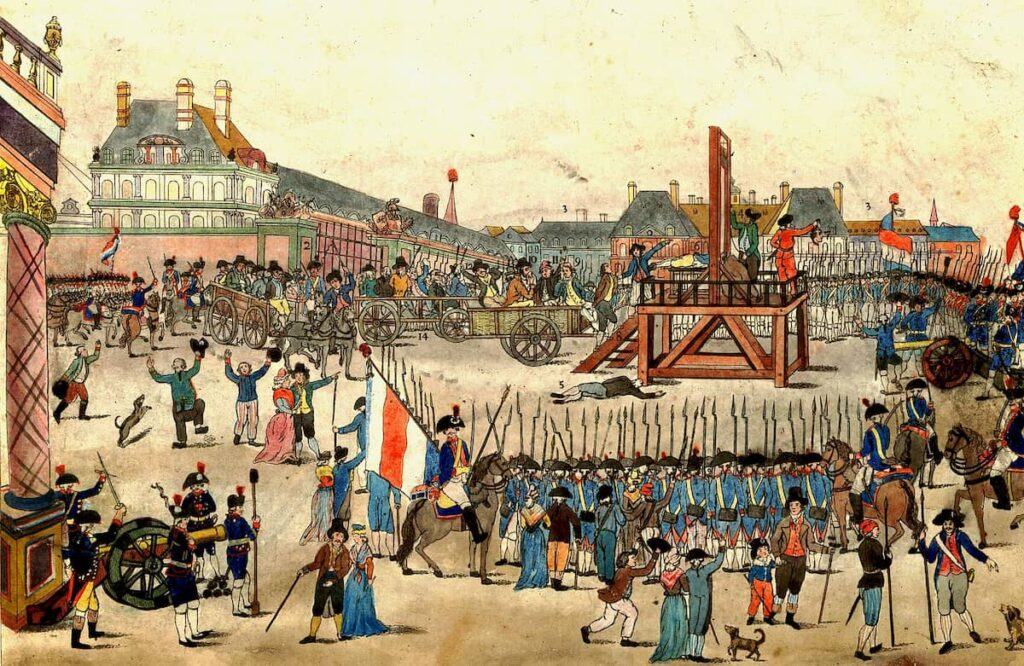

On May 31, 1793, a crowd gathered at the Convention, demanding the expulsion of the Girondins, who were accused of treason. On June 2, the Girondins were placed under house arrest, and on October 31, many of them were guillotined by the verdict of the Revolutionary Tribunal.

The expulsion of the Girondins led to civil war. While France was simultaneously waging war with many European states, the constitution adopted in 1793 never came into force: until peace was achieved, the Convention established a “temporary revolutionary order of governance.” Practically all power was now concentrated in its hands; the Convention sent commissioners to the regions with enormous authority. The Montagnards, who now held significant sway in the Convention, declared their opponents enemies of the people and sentenced them to the guillotine. The Montagnards abolished all seigneurial dues and began selling émigrés’ lands to the peasants. Additionally, they imposed maximum prices on essential goods, including bread; to prevent shortages, they forcibly seized grain from the peasants.

By the end of 1793, most of the rebellions had been suppressed, and the situation on the front turned — the French army went on the offensive. However, the number of terror victims did not decrease. In September 1793, the Convention passed the “Law of Suspects,” which mandated the detention of all individuals who were not accused of any crime but might commit one. From June 1794, the Revolutionary Tribunal abolished the questioning of defendants, their right to lawyers, and the mandatory questioning of witnesses; the only punishment for those found guilty by the tribunal was now death.

Thermidorian Coup

In the spring of 1794, Robespierrists began talking about the need for a final wave of executions to purge the Convention of its enemies. Almost all members of the Convention felt their lives were threatened. On July 27, 1794 (or 9 Thermidor Year II, according to the revolutionary calendar), the leader of the Montagnards, Maximilien Robespierre, and many of his supporters were arrested by Convention members who feared for their lives. They were executed on July 28.

After the coup, the terror quickly subsided, and the Jacobin Club was closed. The power of the Committee of Public Safety was reduced. The Thermidorians declared a general amnesty, and many surviving Girondins returned to the Convention.

Directory

In August 1795, the Convention adopted a new constitution. According to it, legislative power was vested in a bicameral Legislative Corps, and executive power was given to the Directory, composed of five directors chosen by the Council of Elders (the upper house of the Legislative Corps) from a list presented by the Council of Five Hundred (the lower house). Members of the Directory sought to stabilize the political and economic situation in France but were not particularly successful: on September 4, 1797, the Directory, with the support of General Napoleon Bonaparte — who was highly popular due to his military successes in Italy — declared martial law in Paris and annulled the election results in many regions of France, where royalists, now a substantial opposition, had won the majority.

Coup of 18 Brumaire

A new conspiracy brewed within the Directory itself. On November 9, 1799 (or 18 Brumaire, Year VIII of the Republic), two of the five directors, along with Bonaparte, carried out a coup, dispersing the Council of Five Hundred and the Council of Elders. The Directory was also stripped of its power. In its place arose the Consulate — a government consisting of three consuls, all of whom were the conspirators.

Symbols

Napoleon Bonaparte’s Coup and the Establishment of the Empire

On December 25, 1799, a new constitution (the Constitution of Year VIII), created with the participation of Napoleon Bonaparte, was adopted. The government consisted of three consuls, named directly in the constitution, and elected for ten years (as a one-time exception, the third consul was then appointed for five years). Napoleon Bonaparte was named the first of the three consuls. Almost all real power was concentrated in his hands: only he had the right to propose new laws, appoint members of the State Council, ambassadors, ministers, high-ranking military officials, and prefects of departments. The principles of separation of powers and popular sovereignty were effectively abolished.

In 1802, the State Council submitted a referendum on whether Bonaparte should be made consul for life. As a result, the consulate became lifelong, and the first consul gained the right to appoint his successor.

In February 1804, a monarchist conspiracy aiming to assassinate Napoleon was uncovered. Following this, proposals arose to make Napoleon’s power hereditary to prevent such attempts in the future.

Establishment of the Empire

On May 18, 1804, the Constitution of Year XII was adopted and approved by a referendum. The republic was now governed by the “Emperor of the French,” who was declared to be Napoleon Bonaparte.

In December, the emperor was crowned by the Pope.

In 1804, the Napoleonic Code — a set of laws regulating the lives of French citizens — was adopted, drafted with Napoleon’s participation. The Code established, among other things, the equality of all before the law, the inviolability of land ownership, and civil marriage. Napoleon managed to stabilize the French economy and finances: by constantly recruiting soldiers from both rural and urban areas, he resolved the surplus of labor, leading to increased incomes. He harshly dealt with the opposition and restricted freedom of speech. Propaganda, glorifying the invincibility of French arms and the greatness of France, played a massive role.

Symbols

Restoration of the Bourbons and the July Monarchy

As a result of the Napoleonic Wars, the French Empire became the most powerful European state, with a stable governmental system and well-organized finances. In 1806, Napoleon banned all countries under his control in Europe from trading with England; due to the Industrial Revolution, England was displacing French goods from the markets. The so-called Continental Blockade damaged the English economy, but by 1811, the resulting economic crisis affected all of Europe, including France. The French army’s failures on the Iberian Peninsula began to destroy the image of an invincible French army. Finally, in October 1812, the French were forced to begin retreating from Moscow, which they had occupied in September.

Restoration of the Bourbons

From October 16 to 19, 1813, the Battle of Leipzig took place, in which Napoleon’s army was defeated. In April 1814, Napoleon abdicated the throne and went into exile on the island of Elba, while Louis XVIII, the brother of the executed Louis XVI, ascended to the throne.

Power returned to the Bourbon dynasty, but Louis XVIII was forced to grant the people a constitution — the so-called Charter of 1814, according to which every new law had to be approved by two chambers of parliament. Constitutional monarchy was reestablished in France, but not all citizens, or even all adult men, had the right to vote, only those with a certain level of wealth.

Hundred Days of Napoleon

Taking advantage of the fact that Louis XVIII lacked popular support, Napoleon escaped from Elba on February 26, 1815, and landed in France on March 1. A significant part of the army joined him, and in less than a month, Napoleon took Paris without a fight. Attempts to negotiate peace with European countries failed, and he was forced to go to war again. On June 18, the French army was defeated by Anglo-Prussian forces at the Battle of Waterloo, and on June 22, Napoleon abdicated again. On July 15, he surrendered to the British and was sent into exile on the island of Saint Helena. Power returned to Louis XVIII.

July Revolution

In 1824, Louis XVIII died, and his brother, Charles X, ascended the throne. The new monarch took a more conservative course. In the summer of 1829, while the Chamber of Deputies was not in session, Charles appointed the extremely unpopular Prince Jules Auguste Armand Marie de Polignac as Minister of Foreign Affairs. On July 25, 1830, the king signed ordinances (decrees with the force of state law) — temporarily abolishing freedom of the press, dissolving the Chamber of Deputies, raising the electoral property requirement (allowing only landowners to vote), and calling for new elections to the lower house. Many newspapers were shut down.

Charles X’s ordinances caused widespread outrage. On July 27, riots began in Paris, and by July 29, the revolution was over, with major urban centers occupied by the insurgents. On August 2, Charles X abdicated and went into exile in England.

The new king of France became Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans, a representative of the younger branch of the Bourbons, who had a relatively liberal reputation. During his coronation, he swore an oath on the Charter of 1830, drawn up by the deputies, and became not “king by the grace of God,” like his predecessors, but “king of the French.” The new constitution lowered not only the property requirement but also the age requirement for voters, stripped the king of legislative power, banned censorship, and restored the tricolor flag.

Symbols

The Revolution of 1848 and the Establishment of the Second Republic

By the end of the 1840s, the policies of Louis Philippe and his Prime Minister François Guizot, supporters of gradual and cautious development and opponents of universal suffrage, no longer satisfied many: some demanded expanded voting rights, others the return of the Republic and the introduction of suffrage for all. The harvests of 1846 and 1847 were poor, and famine began. Since rallies were banned, political banquets gained popularity in 1847, where the monarchy was actively criticized, and toasts were made to the Republic. In February, political banquets were also banned.

The Revolution of 1848

The ban on political banquets led to mass unrest. On February 23, Prime Minister François Guizot resigned. A huge crowd awaited his exit from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

One of the soldiers guarding the ministry fired a shot — likely by mistake — triggering a violent confrontation. After this, Parisians built barricades and moved towards the royal palace. The king abdicated and fled to England. France was declared a republic, and universal male suffrage for those over 21 was introduced. The parliament (now called the “National Assembly” again) became unicameral.

On December 10-11, 1848, the first general presidential elections were held, unexpectedly won by Napoleon’s nephew, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, who received about 75% of the vote. In the elections to the Legislative Assembly, the Republicans secured only 70 seats.

Symbols

The Coup of 1851 and the Second Empire

The Republicans were no longer trusted by the president, the parliament, or the people. In 1852, Louis-Napoleon’s presidential term was coming to an end. According to the 1848 constitution, he could only be re-elected after another four-year term. In 1850 and 1851, Louis-Napoleon’s supporters repeatedly demanded a revision of this article, but the Legislative Assembly opposed it.

The Coup of 1851: On December 2, 1851, President Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, relying on the army’s support, dissolved the National Assembly and arrested its opposition members. The ensuing unrest in Paris and the provinces was harshly suppressed.

Under Louis-Napoleon’s leadership, a new constitution was drafted, extending presidential powers for ten years. Moreover, a bicameral parliament was restored, with its upper chamber’s deputies appointed for life by the president.

Restoration of the Empire

On November 7, 1852, the Senate, appointed by Louis-Napoleon, proposed the restoration of the Empire. A referendum confirmed this decision, and on December 2, 1852, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte became Emperor Napoleon III.

Until the 1860s, the powers of the parliament were limited, and the freedom of the press was restricted. However, from the 1860s, the course changed. To strengthen his authority, Napoleon began new wars. He planned to overturn the decisions of the Congress of Vienna and reconstruct all of Europe, giving each nation its own state.

The Revolution of 1870 and the Establishment of the Third Republic

In July 1870, the Franco-Prussian War began. From the outset, the French suffered military defeats, and on September 2, Napoleon III himself was captured along with his army. This news shattered the already fragile authority of the emperor in Paris.

Proclamation of the Republic

On September 4, France was proclaimed a republic once again. A provisional government was formed, headed by Adolphe Thiers.

On September 19, the Germans began the siege of Paris. Hunger set in, and the situation worsened. In February 1871, elections were held to the National Assembly, where the monarchists gained the majority. Adolphe Thiers became head of the government. On February 26, the government was forced to sign a preliminary peace treaty, followed by a German parade on the Champs-Élysées, perceived by many Parisians as betrayal.

In March, the government, having no funds, refused to pay the National Guard and attempted to disarm it.

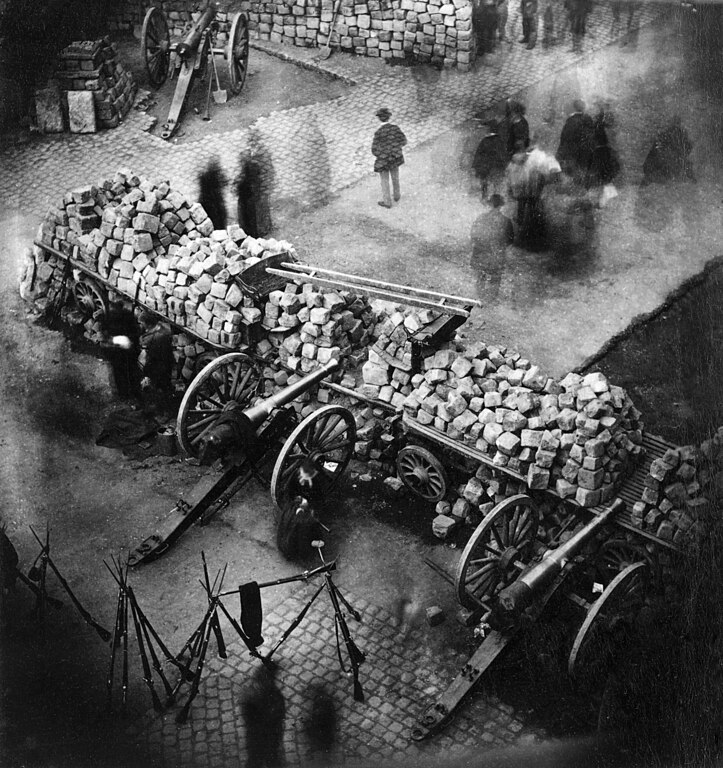

Paris Commune

On March 18, 1871, an uprising broke out in Paris, resulting in a group of left-wing radicals seizing power. On March 26, they held elections to the Paris Commune — the city council of Paris. The government, led by Thiers, fled to Versailles. However, the Commune’s power did not last long: on May 21, government troops launched an offensive. By May 28, the uprising was brutally suppressed — the week of fighting between the troops and the communards became known as the “Bloody Week.”

After the fall of the Commune, the monarchists’ position strengthened again, but since they supported different dynasties, the Republic was ultimately preserved. In 1875, Constitutional Laws were adopted, establishing the position of president and a parliament elected based on universal male suffrage. The Third Republic lasted until 1940.

Since then, France’s form of government has remained a republic, with executive power passing from one president to another through elections.